Kami

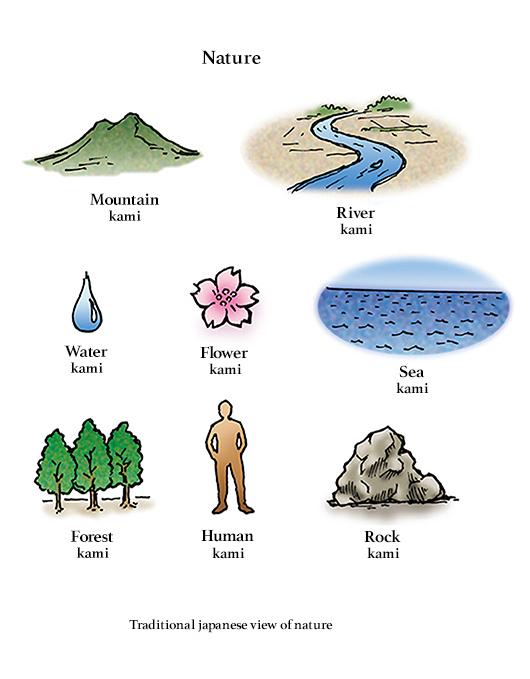

Since ancient times, Japanese have conceptualised the divine energy or life-force of the natural world as kami.

Kami derived from nature, such as the kami of rain, the kami of wind, the kami of the mountains, the kami of the sea, and the kami of thunder have a deep relationship with our lives and a profound influence over our activities.

Nature’s severity does not take human comfort and convenience into consideration. The sun, which gives life to all living things, sometimes parches the earth, causing drought and famine. The oceans, where life first appeared, may suddenly rise, sending violent tsunami onto the land, causing much destruction and grief. The blossom scented wind, a harbinger of spring, can become a wild storm. Even the smallest animals can bring harm—the mouse that eats the grain and carries disease, and the locust that devastates the crops. It is to the kami that the Japanese turn to pacify this sometimes calm but at times raging aspect of nature. The kami are enshrined in sacred spaces called “jinja”, and through ceremonies, called “matsuri”, they are appeased and further blessings requested.

Individuals who have made a great contribution to the state or society may also be enshrined at jinja and revered as kami. The veneration of one’s ancestors is also an important part of the Shinto tradition. This, however, is rarely practised at jinja. Instead, people venerate their ancestors within their homes, as the protecting kami of the household and family.

Shinto accepts no one single, omnipotent Creator. Each kami plays its own role in the ordering of the world, and when faced with a problem, the kami gather to discuss the issue in order to solve it. This is mentioned in texts from the eighth Century which tell the story of the Divine Age before written history began, and is the basis for Japanese society’s emphasis on harmony, and the cooperative utilization of individual strengths.